Analysis of 200+ cases reveals trends in violence against defenders in Philippines

- Posted

- Countries

- Philippines

- Commitments

-

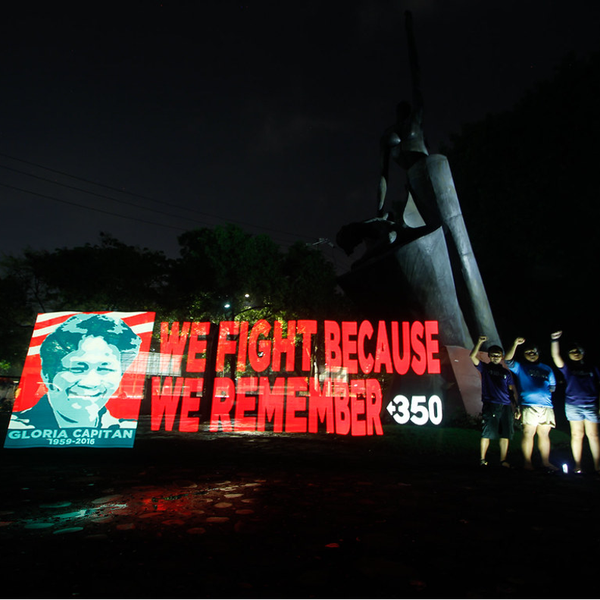

A vigil for anti-coal activist Gloria Capitan who was assassinated in Bataan, Central Luzon, May 2016, from 350.org (2017).

By: Ethan Dockery

The Philippines is consistently described as the most perilous country in Asia and one of the most dangerous countries in the world for land and environmental defenders (LEDs).

Several pieces of state legislation, such as the 1995 Mining Act, aggressively promote natural resource extraction that compromises the land rights of vulnerable communities. The concentration of financial and political power among a small group of elites and rampant corruption have also limited the effectiveness of measures designed to protect LEDs. More recently, incumbent President Rodrigo Duterte has actively encouraged violence against activists (Global Witness 2019). Peaceful LEDs are often ‘red-tagged’ by state actors as communist rebels, a label that often precedes more serious violence in many cases (Amnesty International 2019).

“For every [LED] killed, there are 20 to 100 others harassed, unlawfully and lawfully arrested, and sued for defamation, amongst other intimidations.”

– John Knox, Former UN Special Rapporteur on Human Rights and the Environment.

Working with the data working group of the Alliance for Land, Indigenous and Environmental Defenders (ALLIED), co-led by the International Land Coalition (ILC), my dissertation research focused on data collected from partner organization Environmental Justice Atlas (EJ-Atlas) on violence against land and environmental defenders (LEDs) in the Philippines.

The project diverged from other environmental conflict studies by including data on violence beyond killings. While violent acts like arbitrary detention, defamation and assault are underreported in comparison to murders – due to difficulty of verification, concerns of safety, etc. – they have a huge influence on the everyday lives of LEDs and in many cases, as mentioned, such attacks precede lethal incidents.

The dissertation aimed to address the following questions:

- Are any forms of violence enacted disproportionately against LEDs, and are any of them linked with a higher incidence of murders?

- Are there any identifiable hotspots over space and time in which LEDs are exposed to more violence?

- What underlying drivers or certain types of perpetrators are predominantly responsible for violence against LEDs?

Research Method

The research was largely based on 222 identified cases of violence against LEDs, of which all but 4 occurred between 2000-2021, some coming from EJ-Atlas' database and others identified during independent research. The sources of data on the attacks included articles from local and national newspapers, reports from NGOs and alternative news outlets such as Rappler. Statistical methods were used to analyse the completed dataset and results were complemented by an interview with data specialists at the Asian NGO Coalition (ANGOC), an ILC member organisation.

Key Findings

The research revealed the following key insights about violence against Filipino LEDs:

Types of Violence

Murders were the most frequent form of violence recorded, but in the majority of cases they were accompanied by types of violence beyond killings. Defamation – particularly in the form of red-tagging – was witnessed most often alongside killings (in 57 of 115 cases). While an explicit link was not established between these forms of violence in my analysis, results suggest that additional research and awareness-raising is needed to investigate this relationship further.

Violence Over Space and Time

Over half of the cases originated from the southern island of Mindanao. The presence of communist and Islamic insurgent groups on the island have legitimised repressive violence on the island, particularly during a period of martial law from 2017-19 (Mendoza et al. 2021). The island also harbours many Indigenous ancestral domains, which are frequently targeted by mining and agricultural plantations for development. Additionally, just under half of the entries occurred during the Duterte presidency. This is partially due to the fact that information on older cases was more scarce, but government actions, such as the passing of the 2020 Anti-Terrorism Act, appear to have emboldened perpetrators to employ force within environmental conflicts.

Perpetrators and Drivers

State actors were the most common perpetrators of violence, with the armed forces being the most prolific as both instigators of attacks and contributors in any other capacity. Of non-state perpetrator groups, private individuals– referring predominantly to hired gunmen– appeared more than any other. Findings from secondary sources and interviews, which alluded to state perpetrators hiring gunmen to enact violence on their behalf, implied that collusion between state and non-state perpetrators was likely. Chi-squared test results supported the notion that state security actors and prominent non-state actors cooperated to inflict violence against activists, suggesting that this link needs to be examined more closely in future research.

A bar chart below displays the number of times that certain types of perpetrator instigated a violence entry (blue) or were involved in any capacity (red).

As for drivers behind the violence, environmental conflicts involving mining or land disputes were found to be disproportionately violent, aligning with results from other studies (e.g. Scheidel et al. 2020). Moreover, indigenous LEDs and those working for indigenous rights groups featured in 31% of all cases, far exceeding activists from other organisational affiliations. While the Philippines has previously been identified as one of the most dangerous places for indigenous LEDs (Le Billon and Lujala 2020), this project reinforces existing calls for increased protections for indigenous peoples across the country.

Conclusions

The insights gained from this project demonstrate the importance of considering violence beyond killings in our understanding of the dangers facing LEDs in the Philippines and beyond. Identifying factors that make environmental conflicts more likely to turn violent, such as those involving the armed forces, land disputes or indigenous activists, will help to produce more effective mechanisms that protect LEDs from attacks. However, identifying such risks and patterns will not be possible without the collection of reliable data – encouraging transparent, collaborative data collection is crucial to protect LEDs worldwide as we progress into a future of rapid, uncertain environmental change.

Learn more about ALLIED's work towards a global integrated dataset on LED violence beyond killings, a dataset being built via LANDex.

References

350.org. (2017) Death Anniversary Gloria Capitan. Available online: https://www.flickr.com/photos/350org/34810108554/in/album-72157685732730185/ [accessed 24th September 2021]. Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/

Amnesty International. (2019) Philippines: Stop ‘red-tagging’, investigate killings of activists. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa35/0587/2019/en/ [accessed 24th August 2021].

Dressler, W. (2021) [Forthcoming] ‘Defending lands and forests: NGO histories, everyday struggles, and extraordinary violence in the Philippines’. Critical Asian Studies: 1-32. DOI: 10.1080/14672715.2021.1899834

Global Witness. (2019) Defending the Philippines. London: Global Witness. Available online: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/defending-philippines/ [accessed 17th July 2021].

Global Witness. (2020) Defending Tomorrow: The climate crisis and threats against land and environmental defenders. London: Global Witness. Available online: https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/defending-tomorrow/ [accessed 28th July 2021].

Holden, W. et al. (2011) ‘Exemplifying accumulation by dispossession: mining and indigenous peoples in the Philippines’. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 93(2): 141-161.

Le Billon, P. L. and Lujala, P. (2020) ‘Environmental and land defenders: Global patterns and determinants of repression’. Global Environmental Change, 65: 102163.

Lorch, J. (2021) ‘Elite capture, civil society and democratic backsliding in Bangladesh, Thailand and the Philippines’. Democratization, 28(1): 81-102.

Mendoza, R. U. et al. (2021) ‘Counterterrorism in the Philippines: Review of Key Issues’. Perspectives on Terrorism, 15(1): 49-64.

Scheidel, A. et al. (2020) ‘Environmental conflicts and defenders: A global overview’. Global Evironmental Change, 63: 102104.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2021) Who are environmental defenders? Available online: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/environmental-rights-and-governance/what-we-do/advancing-environmental-rights/who [accessed 18th July 2021].